The MyLoyola login portal allows you to request medical appointments, view your health report from your myLoyola electronic health record, view test results, pay your bills online, and much more.

The MyLoyola login portal allows you to request medical appointments, view your health report from your myLoyola electronic health record, view test results, pay your bills online, and much more.

Or

With myLoyola, one can Schedule or request his/her appointments, Communicate electronically and securely with their medical care team, View lab results, and many more services which can be found at their web portal or mobile application.

MyLoyola Login Guidelines

Step 1: Go to Myloyola’s official login page via our official link below. Once you click on the link, it will open in a new tab for you to continue reading the guide and, if necessary, follow the troubleshooting steps.

Step 2: Simply log in with your access data. You must have obtained it through the Myloyola login page, either by registration or with your permission on the Myloyola sign-in page.

Step 3: Now, you should get the message “Connection successful.” Congratulations, you have successfully connected to the Myloyola login page.

Step 4: If you are unable to log into the site using the Myloyola login page, please follow our troubleshooting guide, which can be found here.

MyLoyola Sign Up Guidelines

- Access the official MyLoyola login page at myloyola.luhs.org.

- Now click on the “REGISTER NOW” button, as shown in the image above.

- Enter your 10-digit activation code from your registration letter or post-visit summary, the last 4 digits of your social security number, and your date of birth in the format provided on the registration page.

- Then click the “NEXT” button and follow the instructions to create your Loyola username and password.

Signup Requirements

- Loyola login web address.

- You need a valid username and password to log in to MyLoyola.

- Web browser.

- PC or laptop or smartphone or tablet with reliable Internet access.

Do One Needs A Myloyola Account To Schedule An Appointment?

No. Making an appointment using the myLoyola self-scheduling tool does not require creating an account. However, creating an account is simple and gives you access to your health record as well as the following features:

- Request medical appointments.

- View test results.

- Access trusted health information resources.

- Communicate electronically and securely with your medical care team.

| Official Name | myLoyola |

|---|---|

| Company | myLoyola |

| Country | USA |

| Language | English & Spanish |

| Type | Login |

MyLoyola Portal Benefits

- Request or schedule an appointment with a medical professional.

- From your myLoyola electronic health record, you can view your health report.

- You can view the test results here.

- You can manage your account online and pay your bills online.

- Data on health can be accessed from trusted sources.

- One can communicate electronically and securely with their medical care team.

My Loyola Chart Mobile Application

MyChart keeps your health information in the palm of your hand, making it easier for you to manage yourself and your family. With MyChart, you can:

- Contact your medical team.

- Review test results, medications, vaccination history, and other medical information.

- Connect your account to Google Fit to pull health data from your personal devices directly to MyChart.

- View a summary of your past hospital visits and stays after the visit, as well as any clinical notes your doctor saved and shared with you.

- Schedule and manage appointments, including personal visits and video-guided tours.

- Get estimates for service costs.

- myLoyola Appointment scheduling.

- View and pay your medical bills.

- Securely share your medical history with anyone with Internet access from anywhere.

- Link your accounts from other healthcare organizations so you can see all of your healthcare information in one place, even if it’s seen with multiple healthcare organizations. Receive automatic notifications when new information becomes available on MyChart. You can check in the app’s account settings whether push notifications are enabled.

Video Visit At MyLoyola Portal

Loyola Medicine offers the ability for patients to have outpatient clinic visits conducted virtually by telephone or a video chat application on your smartphone, tablet, or computer (equipped with a camera and microphone).

If you are interested in changing your existing appointment to a virtual visit, you can contact your physician’s office to schedule.

My Loyola Patients And Visitors

Loyola Medicine has friendly and attentive staff and they always welcome patients and visitors to the Loyola University Medical Center campus, Gottlieb Memorial Hospital, MacNeal Hospital, and their many conveniently located outpatient facilities.

MyLoyola Portal provides the most advanced treatment and treatment for illnesses and conditions. They also care about the whole person. We understand that friends and family help with the healing process.

For patients and visitors, MyLoyola provides comfortable resources and support for stay and accommodation at their centers.

Patient rights

Loyola Medicine is dedicated to excellence in patient care. We want to provide you with care that goes beyond treating your illness or disorder. We are also concerned with the human spirit. Taking care of your well-being is a collaborative effort between you and your Loyola healthcare professionals.

Privacy

Myloyola portal respects the privacy of a patient’s medical records and takes steps to ensure that their medical records remain confidential and secure. With your consent, Loyola Medicine will transmit your electronic medical record to external service providers involved in your treatment. MyLoyola adheres to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Policy. Under HIPAA, Loyola must: 1) ensure that medical information identifying him is kept confidential; 2) inform you of the legal obligations and data protection practices in relation to your medical data, and 3) follow the terms of the notice in effect.

Insurance information

Loyola Medicine accepts many types of insurance, including policies from major insurers, eye and dental insurance, Medicare supplement and replacement insurance, Medicaid, Affordable Care Act plans, and other coverage. Note: Most HMO plans require a referral from your GP. Check with your mutual insurer if you have any questions about their services. If your search results in “out of network” for your insurance plan, check with your insurer to see whether or not you have out-of-network benefits.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are there any charges for using myLoyola?

MyLoyola is a free service for our patients.

How do I get an activation code?

Activation codes will appear on your summary after the last visit and can also be requested at your doctor’s office by requesting in person. You can also contact Loyola’s Medication Consultation at 888-LUHS-888 to receive an email.

Why are you saying my social security number is wrong?

If you get an error saying the last four digits of your social security number are incorrect, we probably didn’t save it. Try entering four zeros (0000) or four eights (8888). If neither 0000 nor 8888 work, contact your doctor’s office to see what’s in store for you.

When can I see my test results on myLoyola?

Your test results are usually uploaded to your myLoyola account within 1-7 days. There are times when the results will be shared with you at the same time your doctor reports them, so you should give your doctor 1-3 days to review and contact you.

I broke up with my Loyola, what happened?

Our goal is to protect your privacy and the security of your data. As long as you are logged into myLoyola and your keyboard has been idle for 15 minutes or more, you will automatically be logged out of myLoyola. We recommend that you exit myLoyola if you need to leave your computer, even for a short period of time.

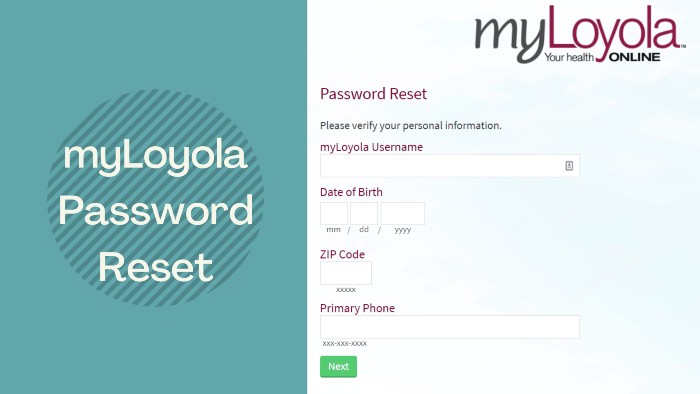

My Loyola Account Password Reset

Patients who have forgotten their myLoyola online account login details can use the self-service tool provided on the portal to submit the necessary data to initiate the recovery process. For that you need

- Visit the myLoyola patient portal at myloyola.luhs.org

- Navigate to the top right corner of the home page and click on the “Forgot my username” or “Forgot my password” link under the “Log in” button depending on your needs.

- Enter your username to reset the password or your first and last name to get the username.

- Then enter your date of birth in MM / DD / YYYY format, your zip code, and your primary telephone number in the fields below.

- Click on the “SEND” or “NEXT” button.

Once your identity is successfully verified, your myLoyola username or a link to reset your password will be sent to you to change your password if you have provided an email address.

If you are unable to set up your email or provide identity verification information, you will need to contact Loyola by phone to regain access to your myLoyola account.

Username Reset

Follow these simple steps below to successfully forget your MyLoyola portal username:

- Go to the official MyLoyola sign-in page at myloyola.luhs.org

- Now click on the “Forgot your password?” Link as shown in the image above.

- Enter Primary’s first name, last name, birth date, zip code, and phone number in the blank space, click the Submit button and follow the instructions to reset your account username.

MyLoyola Appointment Contact Details

You can contact almost any service or department, from paying doctor’s office bills to scheduling procedures or exams, by calling 888-584-7888.

Billing Issues: 800-424-4840

Patient Relations: 708-216-5140

The postal address is:

Loyola drug

2160 S. First alley.

Maywood, IL 60153

Conclusion

It is worth registering for a Myloyola portal as it is a free online patient portal that allows you to safely use the Internet to obtain and store information about your health.

Loyola University Health System offers its patients the free online patient portal, myLoyola, to securely manage, view, and receive their medical information over the Internet. It also provides patients with secure and personalized online access to part of their medical records.